Born July 5, 1958 in Washington, DC, Bill Watterson moved to Chagrin Falls, Ohio, at the age of six, where he and his younger brother lived out their childhood.

Born July 5, 1958 in Washington, DC, Bill Watterson moved to Chagrin Falls, Ohio, at the age of six, where he and his younger brother lived out their childhood.

Even as a child, Watterson would constantly draw cartoons. He later attended Kenyon College in Ohio, graduating with a degree in Political Science in 1980, and later worked as an editorial cartoonist at The Cincinnati Post and as an ad designer, however, Watterson always wanted to draw his own comic strip.

Following his success with Calvin and Hobbes, Watterson won the Reuben Award for "Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year," in 1986, a top award of the National Cartoonists Society, and won it again in 1988 and nominated in 1992.

Watterson set Calvin and Hobbes in an unnamed suburban area that received a lot of snow, greatly resembling Watterson's hometown, however, he insists that Calvin is neither representative of his own childhood or that of his children.

He is very private, keeping to himself and avoiding celebrity at all costs. He does not give out autographs, a ludicrous pastime if I have ever known one, and rarely gives interviews. He keeps an admirably simple life and thus, even with the success of Calvin and Hobbes, the strip never conveyed a change in his demeanor.

Working as an ad designer, a job he disliked, Watterson used any spare time to delve into cartooning, where his passions truly lied. He developed a number of strip ideas, all of which were rejected by all the syndicates submitted, Spaceman Spiff being among the rejected titles. One idea, however, yielded a character with a little brother who had a stuffed tiger, and given positive feedback in that regard, Watterson went to work focusing on the little boy and his  tiger. After a number of new rejections, Universal Press Syndicate finally agreed to take the strip.

tiger. After a number of new rejections, Universal Press Syndicate finally agreed to take the strip.

Calvin and Hobbes was first published on November 18, 1985, only in some thirty-five newspaper, but quickly made history. Within a year, the strip was being published in over 250 newspapers and over 2000 worldwide at the height of the strip's popularity.

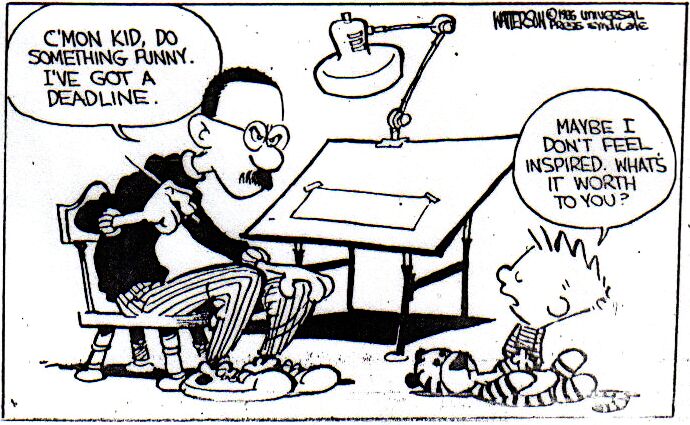

Watterson, thankfully, was the one and only artist to work on Calvin and Hobbes, thus the strip has never strayed from its original quality and vigor. However, remaining on target with the demands of a daily comic strip was tiresome, grueling task and eventually, Watterson took two sabbaticals from the strip, the first spanning from May of 1991 to February of 1992 and the second from April of 1994 to December of 1994.

Sabbaticals notwithstanding, Watterson put much time and effort in his strip, and his endeavors in maintaining the artistic integrity of the series as well as staving off a syndicate pressuring him to market Calvin and Hobbes, pushed Mr. Watterson to end the series' run.

In 1995, Watterson sent a letter to all the editors of newspapers carrying his strip, through his syndicate:

"I will be stopping Calvin and Hobbes at the end of the year. This was not a recent or an easy decision, and I leave with some sadness. My interests have shifted however, and I believe I've done what I can do within the constraints of daily deadlines and small panels. I am eager to work at a more thoughtful pace, with fewer artistic compromises. I have not yet decided on future projects, but my relationship with Universal Press Syndicate will continue. That so many newspapers would carry Calvin and Hobbes is an honor I'll long be proud of, and I've greatly appreciated your support and indulgence over the last decade. Drawing this comic strip has been a privilege and a pleasure, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity. "

"I will be stopping Calvin and Hobbes at the end of the year. This was not a recent or an easy decision, and I leave with some sadness. My interests have shifted however, and I believe I've done what I can do within the constraints of daily deadlines and small panels. I am eager to work at a more thoughtful pace, with fewer artistic compromises. I have not yet decided on future projects, but my relationship with Universal Press Syndicate will continue. That so many newspapers would carry Calvin and Hobbes is an honor I'll long be proud of, and I've greatly appreciated your support and indulgence over the last decade. Drawing this comic strip has been a privilege and a pleasure, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity. "

On December 31, 1995, the last strip ran and Calvin and Hobbes said goodbye.

From the very beginning of the strip's run, Watterson and the syndicate were at constant odds. Universal Press Syndicate wanted him to merchandize the comic and tour the nation, promoting the book collections. Wanting to preserve his work in its true form and disliking any commercialization of his creation, Mr. Watterson, understandably, refused to comply with many of the syndicate's demands.

To him, the art form of the comic strip had become boring and unoriginal due to newspapers devoting less and less space to comics. He wished to display Calvin and Hobbes as comics had been displayed in the 1920s and 1930s, as spanning full pages or even running along several. Newspapers today, only allow a few panels with miniscule space forcing artists to constrain into the limits of the paper, obviously hindering artistic expression.

Feeling that any merchandizing would cheapen the series, Mr. Watterson refused to allow the production of any Calvin and Hobbes merchandise aside from the book collections and two 18-month calendars from the late 1980s. Any figurines, bed sheets, and stickers, including the detestable "Peeing Calvin" t-shirts and bumper stickers, are all illegal bootleg's of Watterson's work.

As an avid lover of Watterson's work, I find myself constantly poring over the book collections and visiting the strip's official website, www.calvinandhobbes.com, as well as many fan sites, such as mine. While I can understand Mr. Watterson's issue with persons merchandising his creation with illegal bootlegs, I cannot fully stand by his and the syndicate's decision to pull websites featuring the strips off the Internet.

One must face the fact that the Internet is changing the way future generations interact with the world. Mainly speaking in that today, it is possible for the words that I type from my apartment in Ohio to be seen in a house in Australia, whereas ten or fifteen years ago, such a medium was not available.

Many new artists do not bother with showcasing their work through comics because of the same limitations that caused Watterson to end his strip, choosing the Internet instead as a way of displaying one's work without any constraints.

Since the comics are available at the official website, they will be subject to "copying" and even if they were not, the books are available and people will always have computer scanners. Removing fan sites like mine, tells me that neither the artist nor the syndicate have a real grasp on how the world is changing, and that artwork, all artwork, must in turn adapt to such changes.

Personally, I have no use for a newspaper. At no charge, I view news stories from several avenues and keep myself up-to-date on the world around me without the nuisance of having to sift through articles about celebrity marriages and left or right wing articles in a medium that is supposed to be unbiased and I know I am not alone in this regard. This poses a problem for newspaper comics in general, which is why there are places where one can view the same comics online.

If newspapers are a dying breed (and I do believe they are and will probably go the way of the radio show in another thirty years), why not be more accepting of a new and unobtrusive media? Had Mr. Watterson created Calvin and Hobbes today instead of twenty years ago, he may have found that the use of the Internet, rather than newspapers, would have allowed him the freedom to continue his artwork, the way he intended it to be made.

Watterson's flair for wanting space to create as well as his refusal to commercialize his work naturally put him at odds with newspaper editors and even a few cartoonists.

Following his return from sabbatical, he demanded half a newspaper page allotted to his strip. This drew flack from editors and some cartoonists such as Bil Keane, both citing that Watterson was arrogant and unwilling to follow normal practices of the trade. Thankfully, he ignored these criticisms.

Bill Watterson has created one of the most brilliant and enduring works of art the world has ever seen. The simple success of book sales, with millions of copies sold worldwide, is evidence in that regard and the existence of sites, such as mine, shows that even though the series has ended, it will ever survive.

I admire Watterson in every regard, from remaining out of the pubic spotlight to his insistence of virtue in his artwork. He demanded a longer forum to display comics as they were meant to be created and got it. During the strip's run he, and only he, wrote and illustrated the comic, taking sabbaticals rather than lend the wheel to another to take away from his creation. The strips were not simply the same jokes over and over and over again, i.e.: Bil Keane's The Family Circus, where there exist two simplified storylines: Billy takes an ultra-long route from Point A to Point B or some comment through a child about the Bible or animals or pants. Watterson's ideas were always fresh and enticing and the artwork, always stunning. Even as a nine-year-old, I grew tired of seeing yet another Sunday panel devoted to one of Keane's characters jumping over fences and running under dogs to go from his bus stop to his front door.

I am still saddened by Watterson's decision to end the strip (even ten years later), but one cannot deny his reasons were valid. Instead of marketing his gift to make all the money he could, Watterson chose to keep the integrity of his artwork and for that I have nothing but awe-inspiring respect for the artist.

My favorite Calvin and Hobbes book collection is the Tenth Anniversary Book, quoted here many times, because the reader can hear Watterson's own words on the how and the why of the strip. In this book, one can see how he struggled with the layout constraints and understand why he was so against commercializing Calvin and Hobbes. While I see myself as a literary artist, I still view Bill Watterson as an inspiration and if (and that is a very big "if") I am ever published and successful, I hope that I can have the strength and determination to stay true to my creations as performed so admirably by the creator of Calvin and Hobbes.